Mark Wallinger, Easter, 2005; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

Mark Wallinger, Easter, 2005; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

Mark Wallinger, Easter, 2005; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

←

→

milan

Pirelli hangar bicocca

23.09 — 27.11.2005

easter

Mark Wallinger

Via Dolorosa, the projected video installation in the Cathedral of Milan might have sufficed on its own, but the encounter with another cathedral – a shrine of more recent metropolitan history, of which the first stone to be laid was The Seven Heavenly Palaces by Anselm Kiefer, has inspired an equally monumental project in Easter, in the still authentic Hangar Bicocca.

Under the canopy of a sky not starry but metallic, Mark Wallinger involves us in a procession with political and religious overtones. But beware, he uses an impossible flag: the United Kingdom’s Union Jack, but with the blue and red replaced by

the complementary colours of the Irish tricolor. In formal terms, it is an oxymoron, inspired in part by W.B.Yeats, ‘A terrible beauty is born’, from Easter 1916. Written about the Irish Nationalist uprisings of that time, this phrase is perhaps the most famous oxymoron in the English language. As with all of Mark Wallinger’s works, Easter does not provide answers but leads to questions: ‘ a new land created in the mind of an artist, or a sign that if you appropriate national symbolism, however illuminated and democratic that might be, the limit of tribal identity becomes clear?’ We would like to offer a collective thank you to Mark Wallinger for having inspired us to show that the primary colours of the ‘terrible beauty’ of Milan have not faded, and that its two cathedrals stand together without putting each other in the shade.

Mark Wallinger, Angel, 1997; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

Mark Wallinger, Easter, 2005; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

←

→

Angel

Mark Wallinger

Projected video installation, audio

7 minutes, 30 seconds,

1997

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God...’ A man (the artist himself) in dark glasses, shaking a white cane, walks on the spot by stepping down on the up escalator, repeating over and over the opening verses of John’s Gospel 1 v.1–5. Blind faith, the Angel, recalls the central Logos of Christianity before ascending to heaven up the escalator to the accompaniment of the music of Handel’s Zadok the Priest. The film unfolds backwards. The redeemed and the damned move fluently backwards up and down the escalators. Everything which happens has already happened. In this work, Mark Wallinger examines questions of faith, predestination and vision.

Mark Wallinger, The Underworld, 2004; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

Mark Wallinger, The Underworld, 2004; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

Mark Wallinger, The Underworld, 2005 — Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan — an © artache project 2005; courtesy: the artist and Anthony Reynolds Gallery, London; Photo Claudio Abate

←

→

The Underworld

Mark Wallinger

21 channel video installation for 21 monitors, audio, continuous loop

2004

The installation consists of 21 monitors turned upside-down and placed on the ground to form a closed circle. Basing the piece on a BBC television broadcast of a live performance of Verdi’s Requiem from 1974, Wallinger recreates that musical masterpiece as a vision of souls in torment. The requiem too is divided into the 21 parts of the liturgy, and the playback of the recording begins at the start of the successive section on each screen: the first monitor starts with part 1 and ends with part 21, the second starts with part 2 and ends with part 1, and so on. Each screen plays the complete work, but in an infinitely circular form. The result of this simultaneous playback of each and all of the movements of the orchestrated liturgy is the generation of a cacophony of sound and images, in an eternally revolving circle. This circle reflects the eternal damnation of the Circles of Hell from Dante’s Inferno. The volume of the musical tumult is shattering. Voices occasionally emerge above it, only to be instantly submerged again. The vocal exertions of the singers engaged in the performance of a work of beauty, spiritual affirmation and redemption are transformed into cries of anguish, panic and fear in the midst of a vast, formless aural chaos. The only light in the room comes from the flickering of the television images.

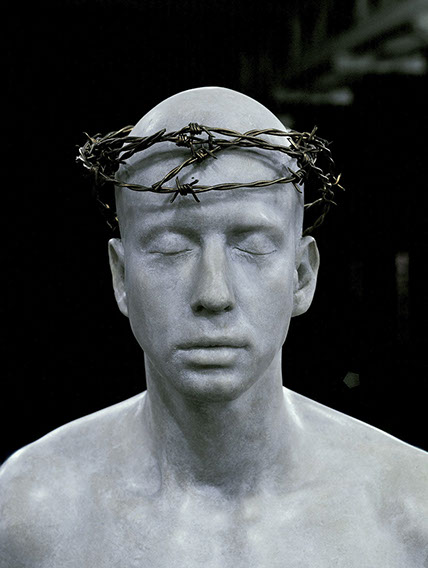

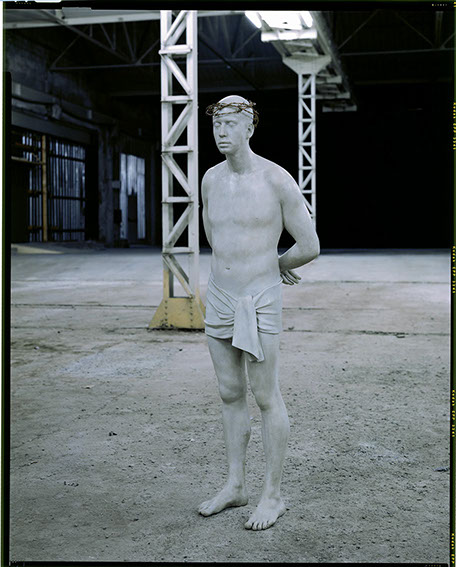

Mark Wallinger, Ecce Homo, 1999-2000; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

Mark Wallinger, Ecce Homo, 1999-2000; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

Mark Wallinger, Ecce Homo, 1999-2000; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

Mark Wallinger, Ecce Homo, 1999-2000; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan; an © artache project 2005; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth © Mark Wallinger; Photo: Claudio Abate

←

→

Ecce Homo

Mark Wallinger

Marbled white resin,

gold barbed wire life-size

1999 - 2000

Ecce Homo! The words of Pilate in John’s Gospel. London, as with most of Great Britain, was cleared of religious statuary during the Reformation. While the Counter Reformation in Latin Catholic countries produced baroque statues of modern saints, in England a hammer was taken to such excesses. Henry VIII instituted the secularisation of Church property, at the same time establishing the royal dynasty at the head of the Church, so it is perhaps even more understandable why there were few examples of public religious art. Ecce Homo was placed on the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square in London from July 1999 to February 2000. A life-size figure of Christ above the multitudes, gazing down over the square, with his hands tied behind his back. The purity of the white statue and the humility of its realistic dimensions contrasts with the bronze vestiges of Empire.

with thanks to

Pirelli Re

Carlo A. Puri Negri

Franca Sozzani

Vogue

Mark Wallinger

Hauser and Wirth

photo

Claudio Abate

graphic design

Archive Appendix

Chiara Figone

video setup

Omero Porta

Icet allestimenti

Mara Vitali

Communication

artache

Graziella Bertolini

Don Luigi Garbini

Viviane Abdel Messih

Stefania Morellato

Credits for artists / photographers and other rightholders have been duly indicated. Should this not be the case, please do let us know. Thank-you.

contact us at info@artache.it

designed by Archive Appendix

artache is not responsible for unauthorized use of the

images, text or any other content of this site by any third

party — all rights reserved © artache 2017